Charlie Wilson’s War is a 2008 film loosely based on the true story of a Texas congressman.

Charlie Wilson’s War is a 2008 film loosely based on the true story of a Texas congressman.

Wilson is best known for leading the US Congress into supporting Operation Cyclone, the largest-ever Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) covert operation which, under the Carter and Reagan administrations, supplied military equipment like the Redeye to the Afghan Mujahedeen during the Soviet war in Afghanistan.

Wilson managed to push funding for the Afghan mujahedeen from $5 million to $1 billion, which led directly to the defeat of the Soviet Union in Afghanistan.

At the end of the film, a CIA officer warns Wilson, celebrating the defeat of the Red Army, that the ‘victory’ may not be all it seems.

He tells the story of a Zen master in a village celebrating a young boy’s new horse as a wonderful gift. ‘We’ll see,’ the master says. When the boy falls off the horse and breaks a leg, the villagers claim the horse is a curse. ‘We’ll see,’ says the Zen master. Then war breaks out, the boy cannot fight because of his broken leg and the people of the village proclaim the horse as a wonderful gift once more. The response of the master: ‘We’ll see.’

Five and a half million Afghans were made refugees by the war – a full third of the country’s pre-war population.

The Soviet Union’s withdrawal from Afghanistan was followed by the civil war which began when the Afghan government was abandoned by the west. By the end of the civil war in 1992, 400,000 Afghan civilians were dead.

Human Rights Watch says that by 2000 some 1.5 million people had died as a direct result of the conflict and 2 million people had been permanently disabled.

With the Taliban in control of most of the country, al Qaeda set up terrorist training camps. On the morning of September 11, 2001, al Qaeda carried out four coordinated terrorist attacks on the United States. The attacks on the Twin Towers and other sites killed 2,996 people, injured over 6,000 others, and caused at least $10 billion in property and infrastructure damage – $3 trillion in total costs.

When America announced the ‘Global War on Terror’, NATO sanctioned the invasion of Afghanistan and later Iraq.

Armed Struggle Becomes Armed Propaganda

In the summer of 1990 I was travelling around Morocco with my two young sons. We had flown from Malaga to Melilla, one of two Spanish enclaves in North Africa (Ceuta is the other). We took a bus to Nador, the first Moroccan city across the border with Melilla. By the end of July, we had reached Tangier, from where we would travel by ferry to Gibraltar.

There had been a palpable increase in tension over the weeks since we had arrived. One evening as we walked along the beach in Tangier, I sat down to write a to my mother back in Ireland. A young Moroccan boy hissed ‘cartes postales’ furiously at us before spitting on the sand and walking off.

We were leaving on the eve of the Iraqi Army’s invasion of Kuwait on 2 August 1990. The Iraqi Army were now within striking distance of the Saudi oilfields. King Fahd immediately appealed for American help to protect his oilfields, and a few days later, the first contingent of US troops trundled into Saudi Arabia.

Today, civilian deaths in Iraq are counted in the hundreds of thousands.

Anyone who doubts the importance of Gibraltar to the British should start with a walk around the Trafalgar Cemetery. Named for the British victory at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805, only two victims of the battle are buried there. The remainder of the graves belong to those killed in other sea battles fought and won by Britain in the area.

The symbolic and strategic significance of the Rock to Britain was graphically illustrated on 6 March 1988 when three unarmed members of the IRA were shot dead by the British Special Air Service (SAS) in Operation Flavius, an undercover exercise targeting them. Intelligence reports had warned that the three, Sean Savage, Daniel McCann, and Mairead Farrell were planning a bomb attack on British troops stationed in Gibraltar.

Plain-clothes SAS soldiers approached them in the forecourt of a petrol station, then opened fire, killing them.

It hardly mattered that the IRA mission had failed. Death on the Rock hit the world headlines hard and the documentary of the same name broadcast by Thames Television the following month was strongly condemned by the British government, while tabloid newspapers denounced it as sensationalist. ‘Death on the Rock’ was the first documentary to be the subject of an independent inquiry, in which it was largely vindicated.

As Gerry Adams wrote in his 1986 book, The Politics of Irish Freedom:

‘The tactic of armed struggle is of primary importance because it provides a vital cutting edge. Without it, the issue of Ireland would not even be an issue. So, in effect, the armed struggle becomes armed propaganda.’

Prepared for Peace, Ready for War

Credits: Wikimedia commons

The Rock is a lodestone for British military, intelligence and economic interests – just 14 km from Africa and close to a key shipping route to the Middle East.

The Royal Air Force (RAF) have a base on the Rock, and there are two British covert surveillance posts on Gibraltar for monitoring communications crossing the Strait between Spain and North Africa. One is a signals station in the north part of Gibraltar. The second is on Gibraltar’s southernmost point, pointing towards Morocco, within a fortified military precinct owned by the UK Ministry of Defence. Ever since the 1970s, the UK has been intercepting Spanish communications from Gibraltar, even though the UK and Spain are military allies.

The base is still used as a stopover for British troops on their way to the Middle East.

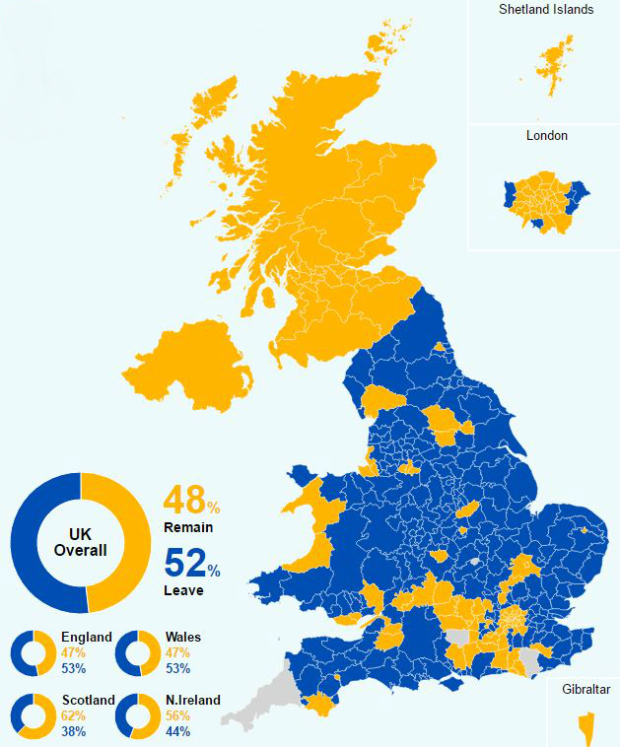

Last June, the UK held a referendum on European Union membership. Northern Ireland, like Scotland, voted to remain, (55.8% and 62% respectively). And although the Remain vote swept the board in Gibraltar with 96%, none of this was enough to alter the eventual UK wide vote: a narrow victory for the Leave side with 52% of the valid vote, compared with 48% who voted to Remain.

On 29 March this year, Theresa May told Parliament that she had triggered Article 50 to start the formal procedure and negotiations for the UK to leave the EU. She had already signed and sent the letter to Donald Tusk, President of the European Council.

The letter strongly hinted that the government hoped to roll the separate issues of security and economic relations together, claiming no deal would mean WTO rules – but added that would mean that ‘our cooperation in the fight against crime and terrorism would be weakened’.

May’s spokesperson said that placing security and trade relations together in the letter to Tusk was not intended as a threat. ‘‘It’s a simple statement of fact that if we leave the EU without a deal, then the arrangements we have as part of our EU membership will lapse,’ he said.

The next week, the EU bit back, raising the issue of Gibraltar in draft EU negotiating guidelines circulated by Tusk, which suggested that Spain would be given a veto over Gibraltar’s participation in a future deal.

The guidelines rocked Westminster to the core, with politicians immediately accusing Spain of using Brexit to make a ‘land grab’ for Gibraltar.

Michael Howard, former Conservative party leader, went so far as to say that Theresa May was ready to go to war over Gibraltar.

In a series of television interviews, Lord Howard repeatedly compared the situation to the Argentine invasion of the Falklands/Malvinas which led to war with the UK. ‘Thirty-five years ago this week, another woman prime minister sent a taskforce halfway across the world to defend the freedom of another small group of British people against another Spanish-speaking country, and I’m absolutely certain that our current Prime Minister will show the same resolve in standing by the people of Gibraltar.’

Just five days since May had invoked Article 50, and the prospect of war with another European state had been broached.

The Hand of History

By 1997 Tony Blair’s Labour government had swept to power. One of Blair’s priorities was to build on the two IRA ceasefires of 1994 and 1996 and he engaged in lengthy talks with Northern Ireland stakeholders and the Irish government.

The Good Friday Agreement had two main elements. One was an agreement between the Northern Ireland parties and the Irish and British governments that the parties would commit to join a power sharing Executive. The other was that Northern Ireland would remain part of the United Kingdom until a majority of both the people of Northern Ireland and of the Republic of Ireland wished otherwise. Should that happen, then the British and Irish governments are under ‘a binding obligation’ to implement that choice.

Posing for the cameras at Stormont, Blair stressed the significance of the Agreement.

‘A day like today is not a day for soundbites, really. But I feel the hand of history upon our shoulders. I really do.’

But is his legacy secure?

‘Dispute not with her, she is lunatic.’

‘Dispute not with her, she is lunatic.’

In its white paper on Brexit the United Kingdom government reiterated its commitment to the Good Friday Agreement. On Northern Ireland’s status, it said that the UK Government’s ‘clearly-stated preference is to retain Northern Ireland’s current constitutional position: as part of the UK, but with strong links to Ireland’.

As former Greek Minister for Finance Yanis Varoufakis warned when he visited Belfast in February, fears that Ireland may end up as ‘collateral damage’ in negotiations between London and Brussels are ‘well-founded.’

Speaking at a meeting of Diem 25 Ireland, Varoufakis pointed out that it was ‘imperative for the Irish government to ensure that it’s not sidelined,’ Specifically in Northern Ireland, it would be ‘criminal’ to do anything to jeopardize the Good Friday Agreement.

‘Bringing back a border and having Northern Ireland be committed to the Brexiteer frenzy coming from the other side of the pond would be madness.’

Asked for his views on Irish unity and if it is legitimate for unionists in Northern Ireland to want to be part of the UK, Varoufakis replied ‘My view would be that, ideally, Europe should be one country and then this discussion doesn’t happen. It is not for somebody like me to tell the people of Northern Ireland anything about their identity. If people want to feel that they are part of Britain, or the United Kingdom, whatever they want to call it, I think that they are perfectly entitled to feel that way. What I can state, broadly, is that borders do not make for happy families and happy societies anywhere…the trick is to find ways of preserving our identities without hiding behind walls, fences and borders.’ Asked if he was in favour of a Federal Europe, Varoufakis replied ‘yes, absolutely’.

On 5th April this year, MEPs adopted another red line. This time, the European Parliament vowed to protect ‘the unique and special circumstances confronting the island of Ireland.’

Manfred Weber, leader of the European People’s Party (EPP) group, warned that the peace process would not be put in danger by the EU’s position during negotiations.

‘If the UK tries to endanger the Irish Good Friday Agreement with the reintroduction of barriers at the Northern Irish border, we will never give our support to an agreement’, he said.

‘Irish interests are not just Irish interests, they are also European interests.’

As Varoufakis pointed out, it would be madness for Northern Ireland, a region which, like Scotland and Gibraltar, voted to remain as part of Europe, to be committed to ‘Brexiteer madness’.

Madness indeed. But as Shakespeare said in Richard III, ‘dispute not with her, she is lunatic.’

Not in My Back Yard

The inconvenient truth is that the existing world order is changing. Talk of borders and frontiers masks the fact that Britain’s interest, as always, is military, strategic and economic. The reality is that UK productivity is 22.7% lower than France, 26.7% lower than Germany, and 10% lower than Italy. Europe is on the skids; and Britain is king of the hill.

Meanwhile, Donald Trump has warned America’s enemies to stay in line or face ‘big, big trouble’ as he sent a warship to Korean waters.

Last week, Trump ‘acted from his gut’ after seeing horrific pictures of child victims in Idlib massacred by chemical weapons and launched 58 Tomahawk missiles from two USS warships. He claimed this was in retaliation for the Syrian chemical weapons attack in Idlib which left more than 80 civilians, including 28 children dead.

The signal was clear – if he finds something unacceptable, anywhere in the world, he will not hesitate to use force. His actions in Syria, he hopes, will put manners on North Korea and Iran.

Donald Trump is a billionaire. He understands that the business of America is war, and war is big business. Trump himself holds stock in Raytheon, the world’s largest producer of guided missiles. After he chose to use Tomahawk missiles, made by Raytheon, the company’s stock rose by 2.1%. Replacing those fired at Syria alone will cost upwards of $100 million.

International diplomacy has been replaced by armed propaganda: the furtherance of strategic, military and economic interests by means of proxy wars.

As Sun Tzu said in The Art of War, ‘The supreme art of war is to subdue the enemy without fighting.’ It is a doctrine that both Donald Trump and Theresa May seem eager to adopt – but not in their own back yard.