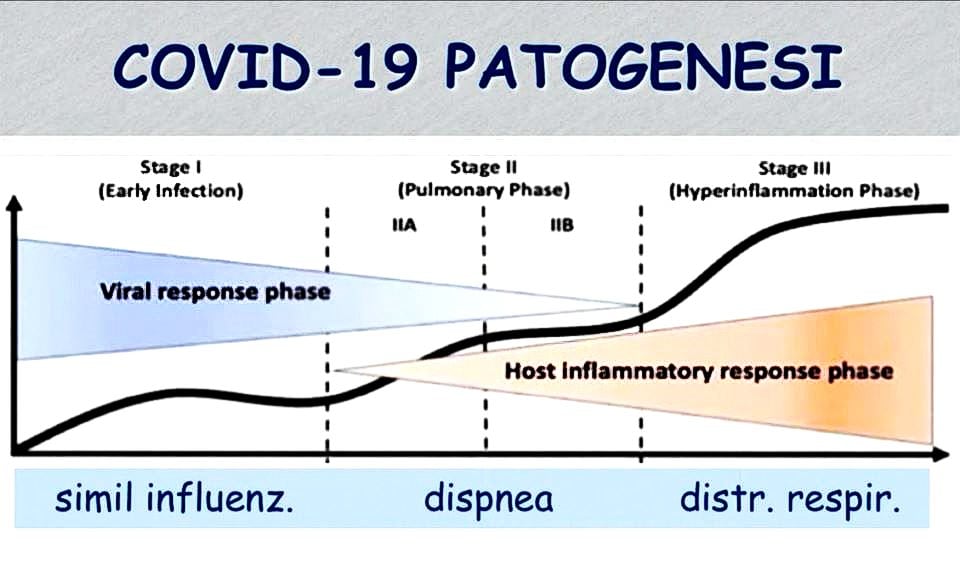

The graph above shows how there are three progressive stages in Coronavirus Disease 2019.

The first one is similar to the common flu and presents mild to no symptoms. Most people heal during this stage and do not progress to the next two. In such cases, nasal and pharyngeal tampons, if done correctly and while the symptoms are showing, mark the presence of the virus.

The second stage is a more severe form that spreads to the lungs (viral pneumonia), from which patients can heal autonomously or with the help of drugs (there are currently ongoing tests with Chloroquine and Azithromycin). Although the pathogen is detectable via tampon in the upper respiratory tract, however, it becomes harder to detect to the point of being untraceable with the onset of pneumonia, since our immune system is responding to the virus and its descent towards our lungs. At this stage, tampons are of little use, since the virus is almost untraceable in both nose and throat, and more invasive methods such as BAL (bronchoalveolar lavage) are necessary to detect it. The radiographic diagnosis is thus bilateral interstitial pneumonia.

In some limited cases (estimated to involve 1% of those infected), the disease advances to its third stage: SARS-cov2 (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome; CoV-2 identifies the virus which caused the COVID-19 pandemic). It is a severe lung disease complicated by Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS), which requires hospitalisation in ICUs with mechanical ventilation. This sharp decrease in pulmonary function is due to an inflammatory reaction which begins during the second stage and then manifests a disproportionate progression unrelated to the virus. The cause is Cytokine Release Syndrome, which triggers excessive production of white blood cells: this extreme immune response can be even more dangerous than the virus itself.

The cause of such worsening is a “disorientation” of the immune system, not the pathogen itself. It is, therefore, a severe autoimmune disease comparable to HLH (Haemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis), a rare immune system disease; in this situation, lung cells are under attack, probably by macrophages. At this stage, the best treatment is a combination of immunosuppressants (such as Ruxolitinib or Tocilizumab) and antivirals (such as Remdesivir) to respond to the viral particles still surviving in the lungs. It would be essential to identify which individuals could be predisposed to this immune dysfunction that leads to a decrease in pulmonary ventilation.

Unfortunately, autoimmune diseases involve many genes, and Sars-CoV-2 is unlikely to be linked to only one genic marker. It would be useful to study the HLAb27 gene, as well as the antibodies appearing in other autoimmune diseases such as Guillain–Barré syndrome, Addison’s disease, coeliac disease, thyroiditis, myasthenia gravis, multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren–Larsson syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus and type-1 diabetes.

Nasal and oral tampons also have several diagnostic limitations, since they can only illustrate a snapshot of the situation and are only useful when the virus is still in the upper respiratory tract. They give no results if the virus has been contracted and then eradicated, or if it made its way to the lungs. Moreover, incorrect execution of the procedure would make tampons ultimately futile. It is, therefore, a methodology that presents many shortcomings when it comes to defining an epidemiological framework of a given territory. It is then necessary to develop an antibody test on blood samples as soon as possible, revealing who contracted the virus and is protected, as well as who is currently ill and contagious. The desirable outcome would be more cost-effective preventive measures until, of course, a vaccine is ready.