The overnight snow had frozen on my windscreen when I left home at dawn on Thursday 12 March 2019.This was originally published in ‘Peace Journalism’ 1 April 2020

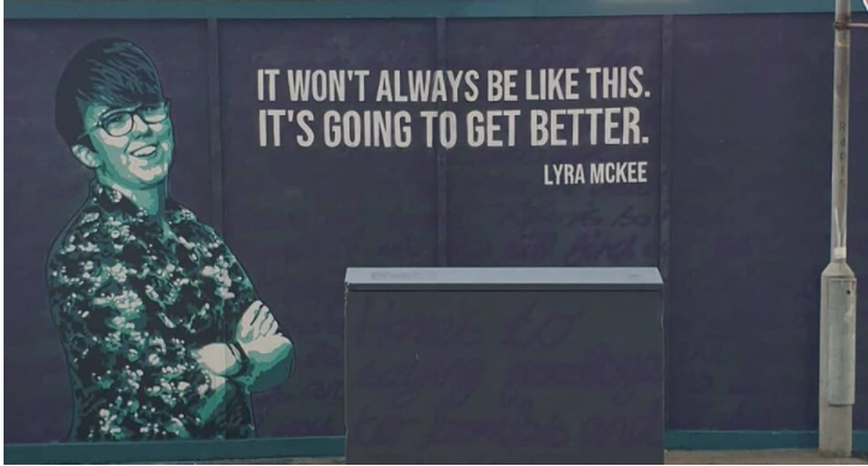

As I drove through Derry, I passed the spot where almost a year ago my friend, colleague, and fellow member of the National Union of Journalists, Lyra McKee, became the latest victim to die in the Northern Ireland Troubles. She was shot dead in Derry by a gunman from the New IRA while observing a riot with other journalists.

Lyra, who was dedicated to investigating the unsolved mysteries of the troubles, would have thrived on these two inaugural workshops where victims and survivors of the troubles, student and practicing journalists, academics and peace builders would discuss the reporting of trauma – and most importantly, hear how it could be improved.

Her life and enthusiasm were at the forefront of my mind at both the Derry and Belfast trauma and journalism workshops on 12 and 13 March 2020.

I spoke of Lyra’s vision, the trauma experienced by her, her partner Sara, and her family, before reflecting on the pain and grief of the years when the political violence that almost tore these islands apart left around 3,700 people dead.

Many more thousands were injured. They, their families, friends and neighbours – and the greater population of Northern Ireland who bore witness to the troubles – bear the scars to this day.

Later I spoke of the bursary which will be established in Lyra’s name to support young journalists engaged in investigative journalism and exploring alternative platforms where narrative and long form pieces might be published. Details are still being finalised but will be announced later on this year.

I was proud to speak in the company of Steve Youngblood from the Centre for Peace Journalism, who discussed socially responsible trauma journalism, Alan Meban and Allan Leonard from FactCheck NI, who spoke of the use of emotive language and alternative websites for fact checking, and Paul Gallagher from WAVE Trauma, a PhD student from Queens University Belfast, who had lost the use of his legs during the troubles. Paul highlighted trauma and victims, pointing out that victims are not homogenous before leading a stimulating discussion on how journalists may compound trauma, and how journalists can contribute to creating a more trauma informed society.

Dr Jake Lynch from the University of Sydney who is also a Visiting Professor at Coventry University this year, shared insights from his ground-breaking work on media interventions for peace during conflict.

Lynch spoke of how the media could structure itself to promote ‘justpeace’ – the concept of justice aligned with peacebuilding pioneered by American Professor of International Peacebuilding at the University of Notre Dame, John Paul Lederach, a frequent visitor to Northern Ireland. After praising VIEWdigital’s Amnesty nominated Victims and Survivors issue, he spoke of Lederach’s ‘justpeace’ approach.

This concept was illustrated by Hands Across the Divide, the sculpture unveiled in Derry in 1992 on the twentieth anniversary of Bloody Sunday, when thirteen unarmed protestors were shot dead in Derry by the Parachute Regiment.

The bronze sculpture of two figures reaching out to each other was a poignant illustration of Lederach’s ‘justpeace’ concept.

The students who made up most of the body of the audience at the Belfast Met on Friday 13 March also heard from Angelina Fusco, the former BBC NI Head of News, who holds a prestigious Ochberg Fellowship awarded by the Direct Action on Research and Training (DART) Centre on Journalism and Trauma.

She was joined by the eminent film maker Sean Murray, whose feature-length documentary investigates the role the British government played in the murder of over 120 civilians in Counties Armagh and Tyrone from July 1972 to 1978 and Barry McCaffrey, an award winning journalist who, with Trevor Birney, whose film, No Stone Unturned, an in-depth look at the unsolved 1994 Loughinisland massacre, where six men were murdered while watching the World Cup at the local pub in Loughinisland, Northern Ireland, remains a touchstone for press freedom in Northern Ireland.